De novo drug design has moved from a niche computational exercise to a central pillar of AI-driven drug discovery. With rising R&D costs, multi-year timelines, and high attrition rates, the ability to generate and optimize molecules directly in silico is no longer a “nice to have” – it is becoming a strategic necessity. A recent review in Frontiers in Hematology systematically maps this emerging landscape, explaining how generative models, rule-based engines, and active learning reshape the way we explore chemical space and progress from target to clinical candidate.

This article distills the key insights of that review and connects them to practical drug discovery workflows, especially in oncology and hematology, where the need for new agents is particularly urgent.

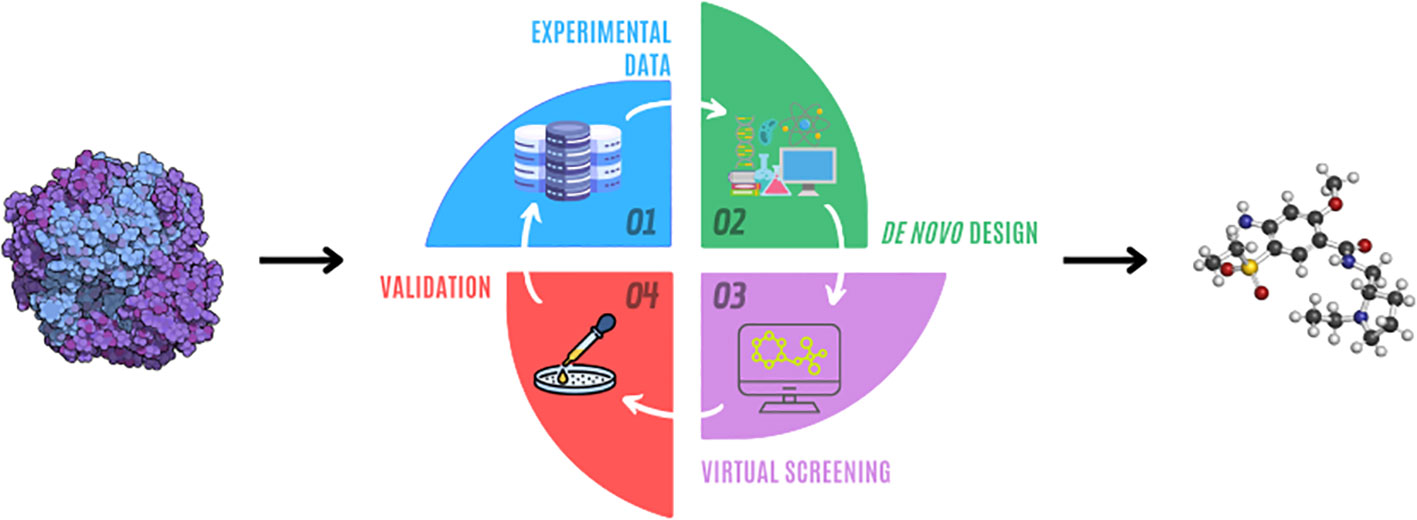

Fig.1 Drug design process.1

Why De Novo Drug Design Matters

Traditional drug discovery is slow, expensive, and risky. Moving from a biological hypothesis to an approved drug typically takes many years and can exceed a billion dollars in total R&D spend. Any efficiency gain in the early design phase has an outsized impact on overall cost and success rate.

De novo drug design addresses a core bottleneck: instead of searching only within existing libraries, algorithms create new, drug-like structures tailored to predefined objectives (e.g., potency, selectivity, ADMET, scaffold novelty). Historically, early de novo tools were limited by:

-

Proposing molecules that were difficult or impossible to synthesize

-

The need for highly specialized computational expertise

-

Limited integration into the experimental “design–make–test–analyze” (DMTA) cycle

The turning point came around 2017, when generative AI models (RNNs, VAEs, GANs, transformers) began to produce chemically valid and biologically meaningful structures at scale. Since then, several AI-designed molecules – such as DSP-1181, EXS21546, and DSP-0038 – have reached clinical trials, proving that generative pipelines can deliver viable clinical candidates, even if most early successes are still focused on well-characterized targets.

Where AI Fits in the Drug Discovery Campaign

The review frames drug discovery as a multi-stage, highly iterative campaign in which AI and de novo design can plug into almost every step.

Target Identification and Validation

The process starts with identifying proteins, genes, nucleic acid motifs, or pathogen components that can be modulated to alter disease progression. AI contributes here mainly by mining large-scale omics and clinical datasets to prioritize targets and validate their disease relevance. Once a target is confirmed, the focus shifts toward finding molecules that modulate it.

Hit Discovery

Traditionally, high-throughput screening (HTS) tests tens of thousands of compounds to find initial “hits.” HTS is powerful but expensive and often inefficient, with low hit rates and high per-compound cost. De novo design offers a complementary path: instead of screening only what is on the shelf, AI explores the enormous theoretical chemical space (estimated at 10³³–10⁶³ drug-like molecules) to propose new structures enriched for the desired properties.

Hit-to-Lead and Lead Optimization

Once initial hits are identified, chemists refine them into “leads” and then into pre-clinical candidates. AI can:

-

Suggest scaffold hops to escape IP or improve selectivity

-

Decorate existing scaffolds with optimized substituents

-

Forecast ADMET and physicochemical properties

-

Propose incremental structural changes to improve potency or safety

Crucially, de novo models can either start from scratch (holistic generation) or build iteratively on known structures, aligning with both hit discovery and lead optimization phases.

Core Design Strategies in AI-Enabled De Novo Discovery

The review summarizes several classical medicinal chemistry strategies and shows how AI boosts each of them.

Chemical Space Sampling

Chemical space sampling selects diverse, representative molecules from enormous theoretical sets, balancing novelty with synthesizability. AI-driven sampling uses fingerprints, descriptors, and generative models to maximize coverage of relevant regions while avoiding unrealistic structures.

Scaffold Hopping and Decoration

-

Scaffold hopping modifies the molecular core while preserving activity, creating structurally distinct yet functionally similar compounds. Generative models trained on diverse scaffolds can propose alternate cores and predict optimal side chains.

-

Scaffold decoration focuses on adding or swapping functional groups around a fixed core to fine-tune potency, selectivity, and ADMET. AI excels at exploring large substituent spaces and learning structure–activity relationships.

Fragment-Based Strategies

Fragment-based design starts from small, low-affinity fragments and builds them into high-affinity ligands by:

-

Linking fragments that bind different subsites

-

Merging overlapping fragments

-

Growing fragments into surrounding pockets

Deep generative models now propose 3D linkers and growth patterns that respect protein geometry, significantly accelerating fragment-to-lead campaigns.

De Novo Design Methods and Molecular Representations

A pivotal part of AI-driven de novo design is how molecules are represented for the model. The review highlights several encoding strategies:

-

String-based encodings (SMILES, DeepSMILES, SELFIES): view molecules as sequences of tokens. SELFIES guarantees syntactically valid strings, an advantage for generative models.

-

Graph-based encodings: represent atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, with optional 3D coordinates. These are natural for graph neural networks and 3D generative models.

-

Feature-based encodings: fingerprints and descriptors summarize molecules by structural or physicochemical features, useful for property prediction and similarity search.

-

Learned latent spaces: autoencoders and related architectures map molecules into continuous vector spaces that can be sampled and optimized, then decoded back into structures.

These representations are trained on large public databases such as ChEMBL, PubChem, BindingDB, DrugBank, GDB-17, QM9, ZINC, and Enamine REAL, as well as structural resources like the Protein Data Bank and UniProt.

Trained Generative vs Rule-Based Engines

The review distinguishes between trained generative models and rule-based systems, each with distinct strengths.

Trained Generative Techniques

-

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)

-

Generate SMILES-like sequences token by token.

-

Early work (e.g., Olivecrona et al., DrugEx) showed they can be fine-tuned for multi-objective optimization, including toxicity and ADMET.

-

-

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) and Latent Space Models

-

Encode molecules into a continuous latent space and decode them back.

-

Enable property-guided latent space navigation and “deep molecular dreaming” where desired properties are back-propagated to generate optimized structures.

-

-

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

-

Use a generator vs discriminator scheme to learn realistic molecular distributions.

-

Examples like ORGANIC, MolGAN, and others highlight utility in molecular optimization but also raise issues around mode collapse and validity.

-

-

Transformer-Based Models

-

Treat molecules as sequences, borrowing advances from NLP (e.g., ChemBERTa).

-

Can suggest chemist-like edits for optimization and learn from huge corpora of unlabeled molecules.

-

Rule-Based Techniques

Rule-based systems predate deep learning and remain powerful because their accessible chemical space is explicitly defined and fully enumeratable. The review highlights:

-

Valence rule spaces (e.g., GDB-17) that list all molecules obeying basic valence constraints.

-

Fragment spaces (BRICS, RECAP) that recombine molecular fragments under human-defined rules.

-

Synthon-based spaces (DOGS, SynthI) that are built from generic reactions and real reagents, directly encoding synthetic feasibility.

-

Matched molecular pair transformations for ADMET and property optimization.

To explore these spaces, algorithms use random mutation of strings (STONED) or evolutionary molecular modification (GB-GA, EvoMol, CoG, SYNOPSIS, GALILEO). These methods are particularly effective for scaffold hopping and late-stage optimization, where chemical intuition is encoded as rules.

Active Learning: Smarter Exploration of Chemical Space

Active learning (AL) introduces an explicit notion of uncertainty into de novo campaigns. Instead of sampling randomly, AL iteratively selects compounds about which the model is least certain, synthesizes/tests them, and retrains. This:

-

Targets under-explored regions of chemical space

-

Improves enrichment factors in virtual screening

-

Reduces the number of experiments needed to find active compounds

Retrospective analyses suggest AL can achieve up to a six-fold enrichment over conventional virtual screening, although real-world adoption is still limited and implementations are often virtual rather than fully automated wet-lab loops.

Virtual Screening, Filters, and Experimental Assays

Because AI can generate far more molecules than can realistically be synthesized, filtering is critical. The review outlines a layered filtering and validation strategy:

Rule-Based Filtering

-

Lipinski’s Rule of Five and QED for oral drug-likeness

-

PAINS and BRENK filters to remove assay-interfering or problematic motifs

-

Synthetic accessibility scores and automated retrosynthetic tools (e.g., AiZynthFinder, AI-driven flow synthesis planners) to prioritize synthetically feasible candidates

Ligand- and Structure-Based Virtual Screening

-

Ligand-based QSAR, pharmacophore modeling, and similarity search for targets with known ligands (less ideal for truly de novo campaigns).

-

Structure-based docking and molecular dynamics simulations, increasingly aided by high-quality protein models from AlphaFold and related technologies. These methods can estimate binding modes and free energies but are computationally expensive, and best used on filtered subsets.

Experimental Validation

Ultimately, candidates must be tested experimentally. The review summarizes:

-

Biochemical assays for direct target engagement and functional modulation

-

Biophysical assays (X-ray, NMR, biophysical binding techniques) for structural and binding detail

-

Cell-based assays for functional readouts in a relevant biological context

Promising compounds then advance to animal studies and, eventually, clinical trials.

How Good Are Current Generative Models?

Evaluating generative models is non-trivial. The review discusses a toolkit of metrics and benchmarks:

-

Internal diversity and richness (number of unique molecules)

-

Fréchet ChemNet Distance (FCD) to compare generated distributions to reference sets

-

Coverage scores and “#Circles” metrics to quantify how much of a reference chemical space is reached

-

Benchmark suites like GuacaMol and MOSES for standardized evaluation in sampling and property optimization tasks

-

Docking-based benchmarks that test whether generated molecules can at least dock as well as top database ligands

Importantly, many models still generate molecules that are hard to synthesize or offer limited novelty relative to existing ligands, especially for well-studied kinase targets. Retrosynthetic analysis tools and synthesizability-aware training are helping, but this remains a key limitation.

Real-World Applications in Oncology and Hematology

The review details several case studies where generative AI contributed to kinase inhibitor discovery and optimization in oncology and hematology:

-

RXR/PPAR dual modulators – RNN-generated SMILES led to several experimentally validated agonists, though with strong resemblance to training compounds.

-

DDR1 inhibitors – Generative models optimized substituents on existing scaffolds to deliver potent and selective kinase inhibitors in weeks rather than months.

-

JAK1 and FLT3 inhibitors – Graph-based VAEs and deep generative models supported scaffold hopping campaigns, yielding new active compounds, albeit with limited novelty in binding modes.

-

SIK2 inhibitors – An AI system combined AlphaFold structures, generative design, and docking to propose candidates; one compound showed excellent in vitro and in vivo activity and favorable ADMET.

Collectively, these case studies confirm that AI is highly effective in hit-to-lead and lead optimization for known targets. The more ambitious goal—discovering structurally and mechanistically novel ligands for poorly characterized targets—remains largely unmet and is a key frontier for the field.

Challenges, Future Directions, and Hybrid Pipelines

The review is deliberately balanced about current limitations:

-

Data bias toward well-explored targets and chemotypes

-

Unclear sampling requirements (how many suggestions to synthesize to reliably get hits)

-

Persistent synthesizability issues for purely model-driven designs

-

High computational cost of structure-based filtering

-

Limited usability of many tools for non-expert chemists

Future progress will likely come from:

-

Synthesizability-aware generative models and better retrosynthetic engines

-

Active learning loops that blend virtual and experimental screening

-

Multi-objective optimization frameworks balancing potency, selectivity, and ADMET

-

Hybrid pipelines combining rule-based, active learning, and trained generative methods in a layered DMTA workflow

The authors envision workflows where active learning identifies promising regions of chemical space, rule-based systems perform early optimization with guaranteed synthetic routes, and generative models perform fine-tuning in the local neighborhood of successful hits.

AI De Novo Design Services at Creative Biolabs

For R&D teams looking to translate these concepts into real projects, Creative Biolabs provides integrated AI-driven de novo design solutions that plug directly into your discovery pipeline, from small molecules to biologics:

-

AI de novo small molecule drug generation – algorithm-driven proposal and ranking of novel, drug-like small molecules for your targets:

-

AI de novo chemical synthesis design – retrosynthesis-aware route planning and synthesizability optimization for AI-generated structures:

-

AI de novo antibody sequence generation – sequence-level design of antibodies with desired binding and developability profiles:

-

Antibody de novo design platform – an end-to-end platform for structural and sequence design of antibody candidates, seamlessly integrated with downstream optimization:

By combining these capabilities with your internal biology and chemistry expertise, you can move from target hypotheses to high-quality AI-generated candidates more quickly, systematically, and confidently.

Reference:

1.Crucitti, Davide, et al. “De novo drug design through artificial intelligence: an introduction.” Frontiers in hematology 3 (2024): 1305741. Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.4c01257