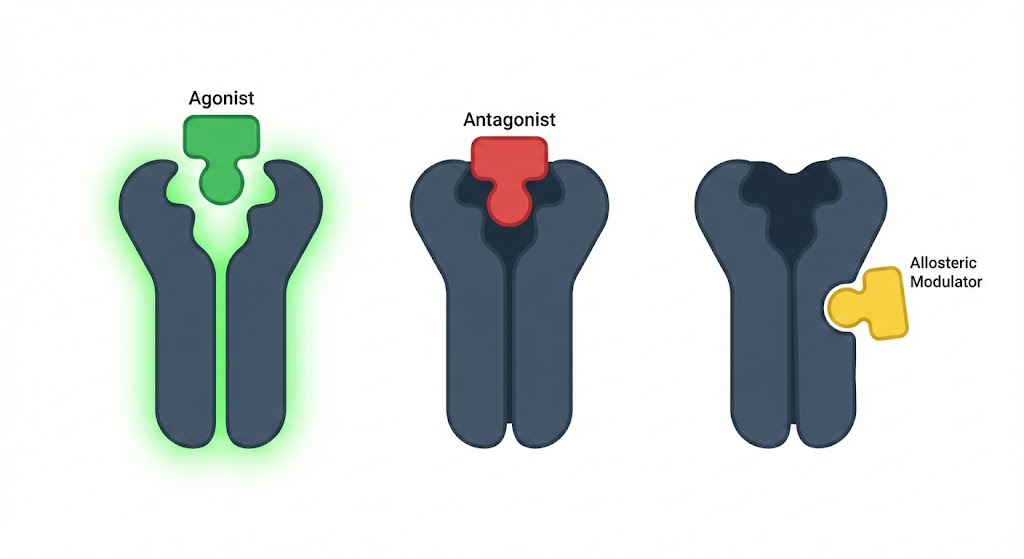

In the landscape of modern drug discovery, the era of simply finding a molecule that “binds” to a target is over. The contemporary challenge lies in functional precision—dictating exactly how a therapeutic agent influences the biological machinery. Whether targeting G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), ion channels, or nuclear receptors, the distinction between an agonist, an antagonist, and an allosteric modulator determines the therapeutic outcome.

For protein engineers and computational biologists, understanding the subtle structural dynamics that differentiate these mechanisms is crucial. It is not merely a question of affinity; it is a question of conformation, kinetics, and thermodynamic landscapes. This guide dives deep into the design principles of these three classes of therapeutics, exploring how Artificial Intelligence (AI) and computational modeling are reshaping how we engineer them.

1. The Orthosteric Playground: Agonists and Antagonists

To understand the design challenge, we must first look at the orthosteric site—the primary binding pocket where the endogenous ligand (the body’s natural signaling molecule) binds.

Agonists: The Architects of Activation

Designing an agonist is arguably the most complex challenge in protein engineering. An agonist must do more than just fit into the binding pocket; it must actively induce or stabilize a specific conformational change that triggers a downstream signaling cascade.

Mechanism of Action: When an agonist binds, it lowers the energy barrier for the protein to shift from an inactive state (R) to an active state (R*). This often involves shifting transmembrane helices (in GPCRs) or inducing domain closure (in kinases).

The Design Challenge:

-

Mimicry vs. Stability: An agonist must mimic the key interactions of the endogenous ligand but often with higher potency or better pharmacokinetic properties.

-

Functional Selectivity (Biased Agonism): Modern design often aims for “biased ligands” that activate one downstream pathway (e.g., G-protein signaling) while avoiding others (e.g., -arrestin recruitment), thereby minimizing side effects.

-

The “Switch” Problem: Computationally, you aren’t just docking a molecule into a static pocket. You must model the transition state. If the molecule binds too tightly to the inactive state, it acts as an antagonist. It must selectively stabilize the active conformation.

Antagonists: The Silent Blockers

Antagonists are inhibitors. They bind to the orthosteric site but do not trigger the conformational change required for signaling. They effectively “jam the lock” so the natural key cannot enter.

Mechanism of Action:

-

Competitive Antagonists: These compete directly with the endogenous ligand for the binding site. Their efficacy relies heavily on concentration and affinity.

-

Inverse Agonists: A distinct subclass that binds to the constitutively active form of a receptor and forces it into an inactive state. This is crucial for diseases caused by overactive receptors.

The Design Challenge:

-

Steric Bulk: Designing antagonists often involves introducing steric bulk that physically prevents the protein from adopting its active shape (e.g., preventing helix movement).

-

Affinity and Residence Time: Unlike agonists, where “turning on” the signal is key, antagonists often benefit from long residence times (slow dissociation rates). The goal is to occupy the receptor for as long as possible.

-

Selectivity: Since orthosteric sites are often highly conserved across protein families (e.g., the ATP-binding pocket of kinases), designing an antagonist that hits only one specific subtype is notoriously difficult.

2. The Allosteric Revolution: Modulation from a Distance

If orthosteric drugs are knocking on the front door, allosteric modulators are sneaking in through the window to rewire the house’s electricity.

Allosteric sites are topologically distinct from the orthosteric site. Binding here causes a conformational ripple effect that alters the protein’s response to the endogenous ligand.

Types of Allosteric Modulators

-

Positive Allosteric Modulators (PAMs): These enhance the affinity or efficacy of the endogenous ligand. They make the receptor “listen harder” to natural signals.

-

Negative Allosteric Modulators (NAMs): These reduce the affinity or efficacy of the endogenous ligand.

-

Silent Allosteric Modulators (SAMs): These bind to the allosteric site but produce no functional change on their own; however, they can block the binding of other allosteric modulators.

Why Design Allosteric Modulators?

-

Superior Selectivity: Orthosteric sites are evolutionarily conserved (to bind the same natural ligand). Allosteric sites are under less evolutionary pressure and are more unique to specific protein subtypes. This allows for highly selective drugs with fewer off-target effects.

-

The “Ceiling Effect” (Safety): A pure agonist can cause an overdose by over-activating the receptor. A PAM, however, only amplifies the body’s natural signal. If there is no natural signal, the PAM has no effect. This intrinsic safety profile is highly desirable in neurology and psychiatry.

-

Modulating “Undruggable” Targets: Some proteins have flat, featureless orthosteric sites (like Protein-Protein Interactions). Allosteric sites often present deeper, more hydrophobic pockets amenable to small molecule binding.

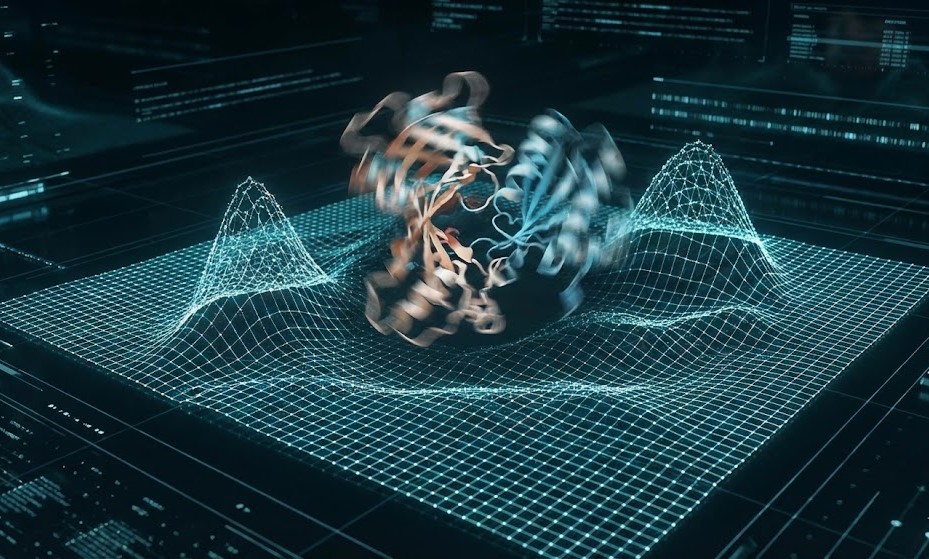

3. Structural Dynamics and Computational Design

The shift from finding binders to designing functional modulators requires a paradigm shift in technology. Static X-ray crystallography is no longer enough. We need to see the protein breathe.

1. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

To design an agonist or an allosteric modulator, we must understand the protein’s energy landscape. *

-

For Agonists: MD simulations allow researchers to observe the transition from Inactive to Active states. We can virtually screen for molecules that lower the energy of the Active state.

-

For Allostery: Long-timescale MD simulations reveal cryptic pockets—binding sites that are only visible when the protein moves. These pockets are invisible in static crystal structures but are goldmines for allosteric drug design.

2. AlphaFold and AI Prediction

AI tools like AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold have revolutionized structure prediction. However, for drug design, we move beyond just predicting the “ground state.”

-

Ensemble Modeling: AI is now being used to generate ensembles of conformations, helping identify transient states that an antagonist might stabilize or an agonist might induce.

-

De Novo Design: Generative AI models (such as diffusion models) can now “paint” new molecules inside these specific pockets, optimizing for shape complementarity and chemical properties simultaneously.

3. Free Energy Perturbation (FEP)

FEP calculations provide high-accuracy predictions of binding affinity.

-

In Antagonist Design: FEP is critical for optimizing the “R-groups” of a molecule to squeeze out every bit of binding energy, ensuring the drug stays bound longer than the natural ligand.

4. Comparative Summary: A Quick Reference

5. The Future: Multi-Targeting and Bitopic Ligands

The frontier of protein therapeutics lies in combining these concepts. Bitopic ligands are molecules that are long enough to span both the orthosteric and the allosteric sites simultaneously.

-

The Best of Both Worlds: These molecules gain the high potency of orthosteric binding with the high selectivity of allosteric binding.

-

AI-Driven Linkers: Designing the “linker” region connecting the orthosteric and allosteric moieties is a geometry problem perfectly suited for Deep Learning algorithms, which can predict the optimal flexibility and length required.

As we move forward, the binary distinction of “on” vs. “off” is being replaced by a dimmer switch. We are no longer just blocking proteins; we are fine-tuning them. Whether through the precise activation of an agonist or the subtle regulation of a PAM, the power lies in understanding the structural biology at an atomic level and utilizing computational prowess to exploit it.

Accelerate Your Protein Therapeutic Design with Creative Biolabs

At Creative Biolabs, we utilize advanced artificial intelligence and computational biology to solve complex structural problems. Whether you need to model protein movements to find allosteric sites or design novel degraders to eliminate targets completely, our platform offers comprehensive support.

Explore our specialized services for your research:

-

AI Protein Modeling Service: High-precision structure prediction and modeling to map orthosteric and allosteric sites.

-

AI Protein Motion Simulation Service: Analyze protein dynamics and conformational changes to understand functional mechanisms.

-

AI Protein Degrader Discovery Service: Develop PROTACs and molecular glues for targets that are difficult to inhibit with traditional methods.

-

AI Protein Degrader Chemical Synthesis Service: Expert chemical synthesis and optimization of your designed protein degraders.

Contact us to learn how our AI-driven solutions can accelerate your drug discovery pipeline.