In the rapidly evolving landscape of therapeutic protein development, the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has shifted the paradigm from “discovery via screening” to “discovery via design.” However, even the most sophisticated deep learning algorithms and generative models are bound by a fundamental rule of data science: Garbage In, Garbage Out.

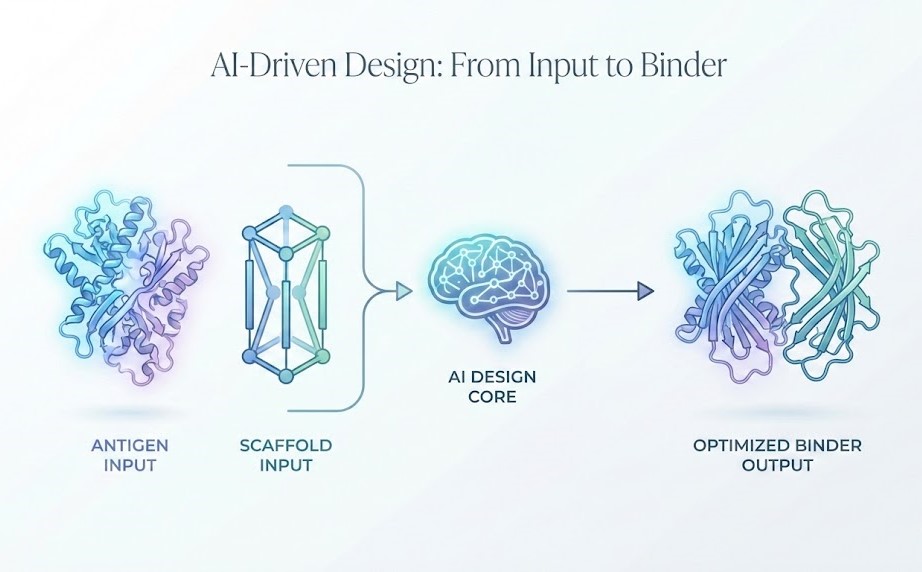

For biopharmaceutical researchers and computational biologists, the quest to create the perfect binder—whether it is a monoclonal antibody, a nanobody, or a non-immunoglobulin protein—does not begin with the algorithm. It begins with the biological inputs. The definition of the antigen and the selection of the structural scaffold are the coordinates that guide the AI. If these coordinates are slightly off, the resulting molecule may have picomolar affinity in silico but fail miserably in the wet lab or clinical setting.

This article explores the critical upstream decisions in antigen and scaffold design that lay the foundation for successful, developable, and potent therapeutic binders.

Why Inputs Matter: The Downstream Cost of Upstream Decisions

In traditional high-throughput screening, you throw millions of variants at a target and see what sticks. In AI-driven de novo design, you are essentially telling a computer to “solve” a geometric and thermodynamic puzzle.

If the input puzzle is defined incorrectly, the solution will be irrelevant.

The “input” in this context is a composite of the target’s biological reality and the therapeutic constraints. Why do these inputs matter so much?

-

Conformational Fidelity: An algorithm designing a binder for a static crystal structure may fail to account for the target’s natural flexibility in a physiological environment. If the input structure doesn’t match the in vivo reality, the predicted binding interface is fiction.

-

Off-Target Toxicity: Poorly defined inputs often focus solely on affinity to the target. However, “better inputs” also include negative design constraints—defining what the molecule must not bind to (e.g., homologous proteins).

-

Developability: A binder designed on a theoretical scaffold without considering stability inputs will likely aggregate. AI models need input constraints regarding solubility and expression levels from day one, not as an afterthought.

By investing time in refining the antigen strategy and scaffold selection, researchers can reduce the attrition rate in the preclinical phase. AI acts as an accelerator; ensure it is accelerating you in the right direction.

Antigen Formats: Beyond Simple Peptides

The antigen is the lock for which we are designing a key. The fidelity of this “lock” determines whether the key will open the door in a patient’s body or only in a test tube.

The Problem with Linear Peptides

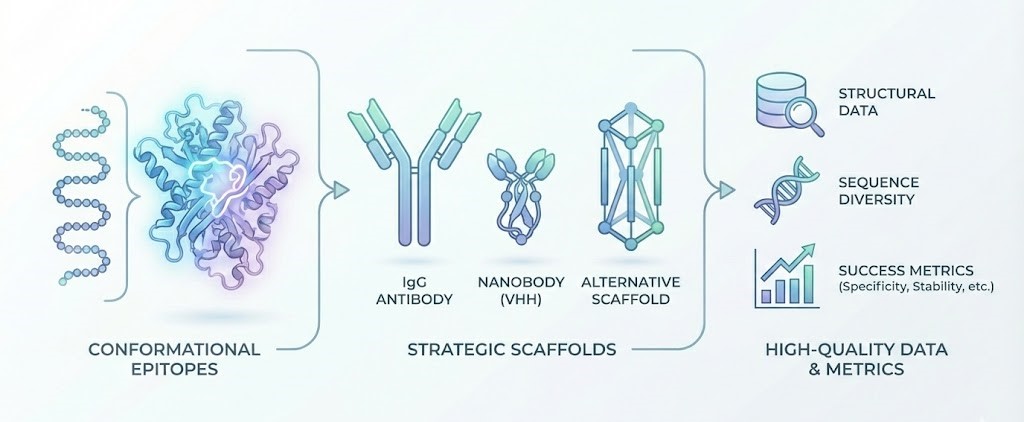

Historically, peptide antigens were popular due to ease of synthesis. However, relying on linear peptides for AI training or binding assays often results in antibodies that bind the peptide perfectly but fail to recognize the native protein. This is because many therapeutically relevant epitopes are conformational—formed by discontinuous amino acid sequences brought together by protein folding.

Recombinant Proteins and Expression Systems

For high-quality AI design, the input data usually relies on 3D structures derived from recombinant proteins. Here, the choice of expression system (E. coli, Yeast, CHO, or HEK293 cells) matters:

-

Glycosylation Patterns: Many surface receptors are heavily glycosylated. If you design a binder using a non-glycosylated crystal structure input, the actual sugar moieties on the native protein might sterically hinder binding.

-

Membrane Proteins: GPCRs and Ion Channels are notoriously difficult inputs. They require lipid environments (nanodiscs or detergent micelles) to maintain their native shape. AI models increasingly utilize Cryo-EM data of these membrane-embedded proteins to predict binders that access extracellular loops accurately.

Epitope Binning and Selection

“Better inputs” also means being specific about where on the antigen you want to bind. Random binding isn’t enough.

-

Functional Epitopes: Binding to the active site to block a ligand.

-

Allosteric Epitopes: Binding to a distant site to induce a conformational change.

-

Cryptic Epitopes: Targeting regions exposed only under specific conditions (e.g., low pH in the tumor microenvironment).

Advanced computational tools now allow us to define the “hotspots” or essential residues on an antigen before the generative design process begins, ensuring the AI focuses its energy on biologically relevant surface areas.

Scaffold Choices: Matching the Tool to the Job

Once the target (antigen) is defined, the next critical input is the scaffold—the structural framework upon which the binding loops (CDRs) or interaction surfaces will be grafted or evolved.

Choosing the right scaffold is not a “one size fits all” decision. It requires balancing size, stability, half-life, and tissue penetration.

1. Traditional Immunoglobulins (IgG)

-

Pros: Long half-life (FcRn recycling), well-understood manufacturing, effector functions (ADCC/CDC).

-

Cons: Large size (~150 kDa) limits tissue penetration; complex folding (two chains).

-

AI Context: There is a massive amount of training data available for mAbs, making AI prediction for IgG backbones highly accurate.

2. Nanobodies (VHH)

-

Pros: Small size (~15 kDa), high stability, can bind hidden epitopes (clefts), easy to engineer into multispecifics.

-

Cons: Short half-life (unless engineered).

-

AI Context: VHHs are becoming a favorite for AI design because they are single-domain proteins. This reduces the computational complexity significantly compared to modeling the heavy-light chain pairing of IgGs.

3. Non-Antibody Scaffolds (DARPins, Anticalins, Knottins)

-

Pros: Extremely stable, free of intellectual property clutter, can be chemically synthesized.

-

Cons: Potential immunogenicity issues in humans.

-

AI Context: These are excellent candidates for de novo design. Because they often have rigid backbones, AI algorithms can focus almost exclusively on mutating the surface residues to create complementarity to the antigen.

The “better input” here is the intentional selection of a scaffold that matches the therapeutic hypothesis. If targeting a dense solid tumor, a VHH scaffold input is superior. If long-term circulating protection is needed, an IgG scaffold is the better input.

Data Requirements: Fueling the Generative Models

In the realm of Creative Biolabs’ AI services, the bridge between the biological concept and the digital execution is Data. The quality of the designed binder is directly proportional to the quality of the datasets used to prompt the AI.

Structural Data

AlphaFold and RoseTTAFold have revolutionized our ability to predict structures, but experimental data (X-ray crystallography, Cryo-EM) remains the gold standard input. Hybrid approaches, where AI predictions are refined by sparse experimental constraints, often yield the best results.

Sequence Diversity and Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs)

To design a robust scaffold, the AI analyzes evolutionary data. Inputs containing deep MSAs allow the model to understand which residues are conserved for stability and which are variable for binding. This prevents the design of a molecule that binds tightly but unfolds at body temperature.

The Importance of “Negative Data”

One of the most overlooked inputs is negative data—sequences that failed to bind. Most public datasets are biased toward successes. However, providing an AI with inputs on what doesn’t work helps carve out the decision boundaries more sharply, reducing false positives in the validation phase.

Success Metrics: How to Measure “Better”

You have selected a high-fidelity antigen and an appropriate scaffold, and the AI has generated candidate sequences. How do we define success? In the era of AI design, we must move the goalposts beyond simple Affinity ($K_D$).

A “better binder” is defined by a multi-parametric success score:

-

Specificity: Does it bind only the target? AI can run “in silico cross-reactivity checks” against a proteome database to predict off-target effects.

-

Solubility & Aggregation: The developability index. High hydrophobic patches on the surface are a red flag. Modern algorithms predict the aggregation propensity score (SAP) as part of the design loop.

-

Thermal Stability ($T_m$): Will the protein survive shelf storage and transport?

-

Immunogenicity: Does the sequence contain T-cell epitopes that will trigger an immune response in the patient? “Humanization” is no longer a post-design step; it is a constraint applied during the generation of the binder.

By setting these success metrics as initial constraints (inputs) rather than final filters, we ensure that the AI navigates the vast chemical space toward molecules that are not just scientifically interesting, but clinically viable.

Empowering Your Research with Creative Biolabs

At Creative Biolabs, we combine state-of-the-art artificial intelligence with deep biological expertise to accelerate your drug discovery programs. From defining the perfect epitope to synthesizing complex protein degraders, our comprehensive suite of AI-driven services ensures your inputs lead to successful outcomes.

Here are some of our recommended services to support your antigen and scaffold design projects:

- AI Epitope Prediction Service:Accurately identify and map linear and conformational B-cell and T-cell epitopes to define precise targets for your binder design.

- AI Antibody Design Service:Utilize advanced generative models to design high-affinity antibodies or nanobodies with optimized developability profiles from scratch.

- AI Protein Degrader Chemical Synthesis Service:Access specialized synthesis capabilities for PROTACs and molecular glues, designed to degrade specific disease-causing proteins.

- AI De Novo Chemical Synthesis Service:Leverage AI planning to execute the synthesis of novel chemical entities and scaffolds with high efficiency and purity.